|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "The essays range far and wide." (Sheldon Kirshner, The Times of Israel, 5 Feb 2017 sheldonkirshner.com and The Times of Israel) The perpetrator-bystander-victim model that has by and large dominated Holocaust scholarship is challenged by the appearance of Soviet Jews in World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering, a collection of essays that examines the role of Soviet Jews as heroes during what the Soviets called the Great Patriotic War. Although the essays in the book cover different types of texts, they are united by a similar set of concerns ... demonstrating that in addition to the breadth of essays present here on the subject of the Holocaust in the Soviet context, the entire Soviet epoch ... is a treasure-trove Naya Lekht, University of California Los Angeles, Slavic and East European Journal 60.4 (Winter 2016) “One of this volume’s most significant achievements is that it contains material that will help educators teach about the Soviet Jewish experience as part of undergraduate courses on the Holocaust. Beautiful translations of Erenburg letters, Selvinskii’s and Slutskii’s poems, and Mikhail Romm’s accounts . . . are among the most valuable key texts, which will change the way the Holocaust is taught in North America. The combination of thorough analysis of new sources with the publication of primary materials make this volume a must-have for anyone interested in Soviet Jewish history and the Holocaust.” Anna Shternshis (University of Toronto) Slavic Review, vol. 74, no. 3 (Fall 2015) “An impressive introduction to new sources and groundbreaking methods in the study of Soviet-Jewish experience during the Second World War. The studies combine an impressive range of critical and historical approaches with solid learning.” "This collection tells stories of Jews in World War II which are practically unknown in the West. These stories are not about the Warsaw Ghetto or Auschwitz, but about Soviet Jewish soldiers, partisans, intellectuals and artists, men and women who fought in the bloodiest battles that the world has known. Drawing on a wide variety of little-known sources, such as private letters, archival documents, memoirs, newspaper reports, novels, poems, photographs and film, this book paints a vivid and dramatic picture of human suffering and heroism." |

|

Soviet Jews At War

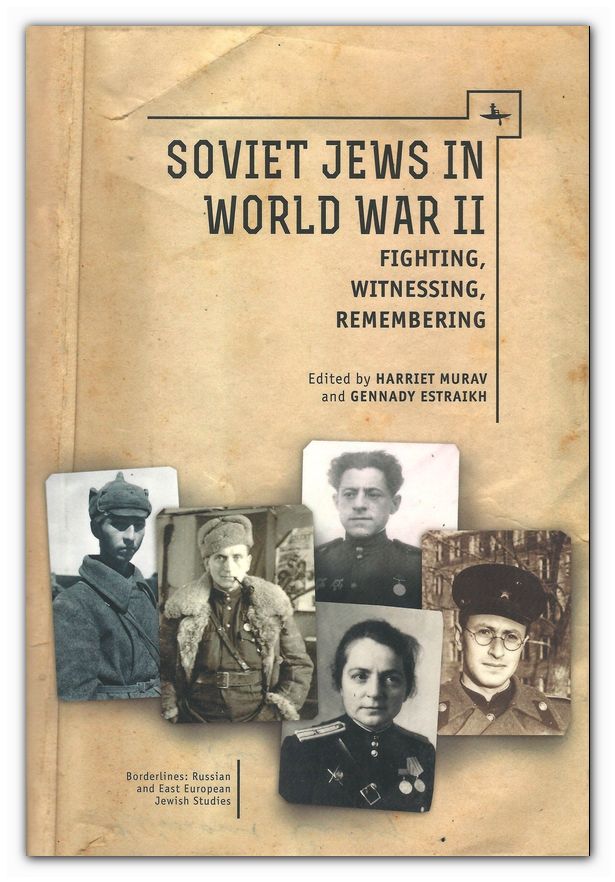

It’s one of the most iconic photographs of World War II. Evgenii Khaldei’s stark black-and-white image of a Red Army soldier holding aloft a Soviet flag over the ruins of Berlin, circa April 1945, still resonates. Dubbed “Raising the Red Flag Over Reichstag,” the photograph speaks to the military victory of the Soviet Union over Nazi Germany. Khaldei, a Russian Jew, photographed the war in all its permutations from beginning to end, and was one of many Jews who worked as photographers, propagandists and journalists in the service of the Soviet Union during its four-year epic struggle with Germany. In large part, they created the Soviet narrative of the war. Upwards of 500,000 Jews fought with the Soviet armed forces during that dark period, and of these, 142,500 lost their lives in defence of the motherland. As they laid down their lives on the far-flung battlefields, the Nazis murdered 2.5 million Jewish civilians in the territories comprising the Soviet Union. Soviet Jews In World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering, a book of eclectic essays co-edited by Harriet Murav and Gennady Estraikh and published by Academic Studies Press, examines their variegated role in the Great Patriotic War. The editors claim that this volume is one of the first to draw on Russian and Yiddish materials. The essays, which vary in quality, were originally presented at a conference, Soviet Jewish Soldiers, Jewish Resistance and Jews in the USSR during the Holocaust, in 2008. The conference was jointly sponsored by the U.S. Holocaust Museum, the Blavatnik Archive Foundation and the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University. The essays range far and wide. In Jewish Combatants of the Red Army Confront the Holocaust, Mordechai Altschuler says that Jewish soldiers discovered the enormity of the Holocaust after returning to their respective towns. “This feeling of orphanhood, which was common among many Jewish combatants in the Red Army, stood in sharp contrast to the expressions of antisemitism they experienced from local residents and sometimes even among their own comrades,” he writes. At the start of the war, he explains, crude manifestations of antisemitism in the ranks of the Red Army were rare. But as the tide turned against the Germans, Russian “feelings of chauvinism” surfaced.

Joshua Rubenstein, in Il’ia Ehrenburg and the Holocaust in the Soviet Press, describes that Jewish journalist as “the most significant voice in the Soviet press during World War II.” Writing primarily for Red Star, a newspaper distributed to Red Army soldiers, Ehrenburg was widely read and admired. So much so that the Soviet foreign minister once said that he was worth a division. Cognizant of Ehrenburg’s fame, Adolf Hitler promised to hang him in Red Square after Germany’s capture of Moscow. Ehrenburg was one of the few journalists to write about the Holocaust in the Soviet media. “Under appalling conditions, constrained by wartime deprivations, Soviet censorship and indifference to Jewish suffering, he did what he could to alert the Soviet public and the West,” Rubenstein writes. He adds, “It is undeniably true that the Soviet press did not cover the mass murder of its Jewish citizens with anywhere near the prominence it deserved. But it is a falsification of the historical record to claim that the press did not cover it at all.” Gennady Estraikh, in Jews as Cossacks: A Symbiosis in Literature and Life, examines a fascinating topic. Although Russian Cossacks were inextricably associated with pogroms in czarist Russia, and thereby regarded as enemies of the Jewish people, Jews nonetheless joined Cossack military units. “I have not come across any statistics of Jewish participation in the Red Army cavalry detachments, though it is known that Jewish cavalrymen fought in various regiments and divisions, including Cossack ones,” Estraikh observes. Citing the case of a Jew who joined a Cossack detachment, Estraikh says, “According to him, he never had problems with being a Jew among non-Jewish cavalrymen.” Some Jewish novelists, like Zalman Lifshits and Isaac Babel, wrote about Cossacks with varying degrees of hostility and sympathy, he notes. Gen. Yakov Kreizer (Wikimedia)

Arkadi Zeltser’s essay, How the Jewish Intelligentsia Created the Jewishness of the Jewish Hero: The Soviet Jewish Press, focuses on Eynikayt, the Yiddish house organ of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which was eventually disbanded by Joseph Stalin. Apart from singing the praises of Jewish war heroes like Gen. Yakov Kreizer, Eynikayt paid attention to Jewish ghetto uprisings in Polish cities like Warsaw and Bialystok. Interestingly enough, as Zelster points out, Lazar Kagonovich, a Jewish member of the ruling Politbureau and a confidant of Stalin, played a role in shaping popular perceptions of Soviet Jews. In 1937, after attending a performance of a play at the Moscow State Yiddish Theater, he demanded that stereotypical shtetl Jews should be replaced by “heroic images of the Jewish past, like the Maccabees.”

Olga Gershenson, in Between the Permitted and the Forbidden: The Politics of Holocaust Representation in The Unvanquished, writes about the world’s first Holocaust film. Released in October 1945, shortly after the end of the war, Unvanquished was filmed on location in Babi Yar, where 33,000 Jews had been killed. Based on a novel by Boris Gorbatov which had been serialized in Pravda in 1943, Unvanquished was directed by one of the greatest directors of the day, Mark Semenovich Donskoi, an assimilated Jew. The film was chosen to represent the Soviet Union at the Venice Biennale in 1946, but in 1948 it vanished from view, not to be seen again until the 1960s, when it was shown on Soviet TV. “The film’s reception reflected the ambivalent Soviet policies of the time, when the topic of the Holocaust was neither completely suppressed nor fully acknowledged, but vacillated in the grey area between the allowed and the forbidden,” Gershenson writes. David Shneer’s essay, From Photojournalist to Memory Maker: Evgenii Khaldei and Soviet Jewish Photographers, brings us back to square one. Khaldei, born in what is now the eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk, gained fame during the war, particularly with “Raising the Red Flag over the Reichstag.” But Khaldei also documented Nazi atrocities against Jews, a topic that Ogonek, the popular Soviet magazine, first covered in the summer of 1941. As Shneer suggests, Khaldei, along with Jewish colleagues such as Max Alpert and Aleksandr Grinberg, were in the forefront of documenting the building of Soviet society. When war broke after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, they turned their gaze to the battlefield. Evgenii

Khaldei (Wikimedia)

In 1948, amidst Stalin’s antisemitic campaign, Khaldei was laid off from his job at the TASS news agency. TASS rehired him after Stalin’s death in 1953, but Khaldei never regained his old prestige. Such was life in the Soviet Union, particularly for a Jew. |

Эта публикация в открытом доступе является частью проекта, поддержанного Фондом Эндрю У. Меллона — инициативы «Открытая книга гуманитарных наук», в рамках которой публикуется ряд академических исследований в формате открытого доступа.

Благодарности

Мы выражаем глубокую благодарность Мемориальному музею Холокоста США,

Фонду Блаватник, а также отделу скибола по ивриту и иудаике в

Нью-Йоркском университете за спонсорство конференции, на которой

основан данный том. Мы также признательны Фонду по изучению Холокоста в

СССР, Центру перспективного изучения Холокоста Мемориального музея

Холокоста США, Нью-Йоркскому университету и программе по еврейской

культуре и обществу в Университете Иллинойса в Урбана-Шампейн за их

щедрую поддержку этой публикации.

В этом томе рассматривается участие евреев как солдат, журналистов и пропагандистов в борьбе с нацистами в годы Великой Отечественной войны — как назывался в Советском Союзе период с 22 июня 1941 года по 9 мая 1945 года. Представленные здесь эссе исследуют как недавно обнаруженные, так и ранее забытые устные свидетельства, поэзию, кино, дневники, мемуары, газетные публикации и архивные материалы. Это одна из первых книг, в которой объединяются источники на русском и идиш, отражающие специфику Еврейского антифашистского комитета, в состав которого впервые за советский период вошли писатели, работавшие как на идише, так и на русском языке. Этот том будет полезен учёным, преподавателям, студентам и исследователям, занимающимся русской и еврейской историей.

«Модель „преступник — свидетель — жертва“, которая в целом доминировала в научной литературе по Холокосту, подвергается сомнению благодаря появлению сборника „Советские евреи во Второй мировой войне: борьба, свидетельство, память“. В нём рассматривается роль советских евреев как героев Великой Отечественной войны. Хотя эссе охватывают разные жанры и формы, их объединяет общий круг вопросов… Эти тексты показывают, что наряду с темой Холокоста в советском контексте вся советская эпоха представляет собой сокровищницу, которая ещё ждёт своего изучения».

— Найя Лехт, Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе, Slavic and East European Journal, том 60.4 (зима 2016)

«Одним из самых значимых достижений этого тома является публикация материалов, которые помогут преподавателям рассказывать о советском еврейском опыте в рамках курсов по Холокосту. Прекрасные переводы писем Эренбурга, стихи Сельвинского и Слуцкого, а также рассказы Михаила Ромма — это одни из самых ценных ключевых текстов, способных изменить подход к преподаванию Холокоста в Северной Америке. Сочетание глубокой аналитики и публикации первоисточников делает этот том обязательным для всех, кто интересуется советской еврейской историей и темой Холокоста».

— Анна Штерншис, Университет Торонто, Slavic Review, том 74, № 3 (осень 2015)

«Впечатляющее введение в новые источники и новаторские методы исследования советско-еврейского опыта во время Второй мировой войны. Сборник объединяет широкий спектр критических и исторических подходов и отличается высоким академическим уровнем».

Советские евреи на войнеЭто одна из самых знаковых фотографий Второй мировой войны. Яркий черно-белый снимок Евгения Халдея, на котором солдат Красной Армии водружает советский флаг над руинами Берлина в апреле 1945 года, до сих пор вызывает отклик. Эта фотография, получившая название «Поднятие красного флага над Рейхстагом», символизирует военную победу Советского Союза над фашистской Германией. Халдей, русский еврей, документировал войну от начала до конца и был одним из многих евреев, работавших фотографами, пропагандистами и журналистами на службе Советского Союза в годы его четырёхлетней эпической борьбы с Германией. Именно они в значительной мере сформировали советское повествование о войне. Более 500 000 евреев сражались в составе советских вооружённых сил в этот мрачный период, и 142 500 из них погибли, защищая Родину. Пока они отдавали свои жизни на бескрайних полях сражений, нацисты уничтожили 2,5 миллиона еврейских мирных жителей на территориях, входивших в состав Советского Союза. «Советские евреи во Второй мировой войне: сражаться, свидетельствовать, вспоминать» — сборник эклектичных очерков под редакцией Харриет Мурав и Геннадия Эстраиха, изданный Academic Studies Press, — рассматривает разнообразную роль советских евреев в Великой Отечественной войне. Редакторы подчёркивают, что это один из первых томов, в котором используются материалы как на русском, так и на идиш. Эссе, различающиеся по уровню исполнения, были впервые представлены на конференции «Советские евреи-солдаты, еврейское сопротивление и евреи в СССР во время Холокоста», прошедшей в 2008 году. Конференция была организована при финансовой поддержке Мемориального музея Холокоста США, Архивного фонда Блаватник и отдела ивритских и иудаистических исследований Нью-Йоркского университета. Тематика эссе охватывает широкий спектр сюжетов. В статье «Еврейские бойцы Красной Армии, противостоявшие Холокосту» Мордехай Альтшулер отмечает, что еврейские солдаты столкнулись с масштабами Холокоста, когда вернулись в свои разрушенные города. «Это чувство сиротства, охватившее многих еврейских бойцов Красной Армии, резко контрастировало с проявлениями антисемитизма, с которыми они сталкивались со стороны местных жителей, а порой и со стороны собственных товарищей», — пишет он. Он поясняет, что в начале войны открытые проявления антисемитизма в рядах Красной Армии были редки. Но когда ход войны повернулся против Германии, русские «шовинистические настроения» начали всплывать на поверхность. Джошуа Рубинштейн в эссе «Илья Эренбург и Холокост в советской прессе» называет этого еврейского журналиста «самым значительным голосом в советской прессе времён Второй мировой войны». Прежде всего он писал для газеты Красная звезда, которая распространялась среди солдат Красной Армии. Эренбург пользовался широкой популярностью и вызывал восхищение у читателей. Настолько, что советский министр иностранных дел однажды заявил: «Он стоит целого фронта». Осознавая влияние Эренбурга, Адольф Гитлер пообещал повесить его на Красной площади в случае взятия Москвы. Эренбург был одним из немногих журналистов, писавших о Холокосте в советской прессе. «В ужасающих условиях, связанных с лишениями военного времени, советской цензурой и общим равнодушием к страданиям евреев, он сделал всё возможное, чтобы предупредить советскую общественность и Запад», — пишет Рубинштейн. Он добавляет: «Несомненно, советская пресса не освещала массовые убийства своих еврейских граждан с той полнотой и авторитетом, которых они заслуживали. Но утверждение, будто пресса вообще не упоминала об этом, — это фальсификация исторических фактов». Геннадий Эстраих в книге «Евреи как казаки: симбиоз в литературе и жизни» исследует поразительную тему. Несмотря на то что русские казаки были неразрывно связаны с еврейскими погромами в дореволюционной России и традиционно считались врагами еврейского народа, евреи всё же вступали в казачьи войска. «Я не встречал достоверной статистики об участии евреев в кавалерийских частях Красной Армии, хотя известно, что еврейские кавалеристы служили в различных полках и дивизиях, включая казачьи», — отмечает Эстраих. Ссылаясь на случай еврея, вступившего в казачий отряд, он пишет: «По его словам, у него никогда не возникало проблем с тем, чтобы быть евреем среди нееврейских кавалеристов». Некоторые еврейские писатели, такие как Залман Лифшиц и Исаак Бабель, в своих произведениях писали о казаках — с различной степенью враждебности и сочувствия, подчёркивает Эстраих. Генерал Яков Крейзер (Викимедиа)

Эссе Аркадия Зельцера «Как еврейская интеллигенция создала еврейство героя-еврея: советская еврейская пресса» посвящено газете Эйникайт, официальному органу Еврейского антифашистского комитета, издававшемуся на идише и в конечном итоге распущенному по приказу Иосифа Сталина. Помимо прославления еврейских героев войны, таких как генерал Яков Крейзер, Эйникайт также освещал восстания в еврейских гетто польских городов — Варшавы, Белостока и других. Интересно, как отмечает Зельцер, что Лазарь Каганович, еврей — член правящего Политбюро и доверенное лицо Сталина, сыграл немаловажную роль в формировании массового образа советских евреев. В 1937 году, после посещения спектакля в Московском государственном театре на идише, он потребовал заменить стереотипные образы штетльских евреев «героическими фигурами еврейского прошлого, такими как Маккавеи». Ольга Гершенсон в книге «Между разрешённым и запрещённым: политика представления о Холокосте в фильме „Непобедимый“» пишет о первом в мире художественном фильме, посвящённом теме Холокоста. Премьера фильма «Непобедимый» состоялась в октябре 1945 года, вскоре после окончания войны. Съёмки проходили, в том числе, на месте массового убийства в Бабьем Яру, где были расстреляны 33 000 евреев. Сценарий был основан на романе Бориса Горбатова, опубликованном в виде сериала в газете Правда в 1943 году. Режиссёром картины стал один из крупнейших советских кинематографистов своего времени — Марк Семёнович Донской, еврей по происхождению, выросший в ассимилированной среде. Фильм был выбран для представления Советского Союза на Венецианской биеннале 1946 года, но уже в 1948 году он исчез из публичного пространства. Лента оставалась недоступной вплоть до 1960-х годов, когда её показали по советскому телевидению. «Приём фильма отражает двойственную политику советских властей того времени: тема Холокоста не была ни полностью запрещена, ни открыто признана — она колебалась в серой зоне между дозволенным и запретным», — пишет Гершенсон. Эссе Дэвида Шнеера «От фотожурналиста до хранителя памяти: Евгений Халдей и советские еврейские фотографы» возвращает нас к фигуре, уже ставшей символической. Евгений Халдей, родившийся в ныне украинском городе Донецке, приобрёл известность во время войны, особенно благодаря фотографии «Поднятие красного флага над Рейхстагом». Но он также документировал нацистские преступления против евреев — тему, которую впервые затронул Огонёк, популярный советский журнал, уже летом 1941 года. Как подчёркивает Шнеер, Халдей, наряду с другими еврейскими фотографами — такими как Макс Альперт и Александр Гринберг, — оказался в первых рядах тех, кто документировал строительство советского общества. Когда началась война с Германией, их камеры были направлены на поле боя. Евгений Халдей (Викимедиа) В 1948 году, в разгар сталинской антисемитской кампании, Евгений Халдей был уволен из агентства ТАСС. После смерти Сталина в 1953 году ТАСС вновь приняло его на работу, но Халдей так и не смог вернуть прежний статус и авторитет. Такой была жизнь в Советском Союзе — особенно для еврея. |